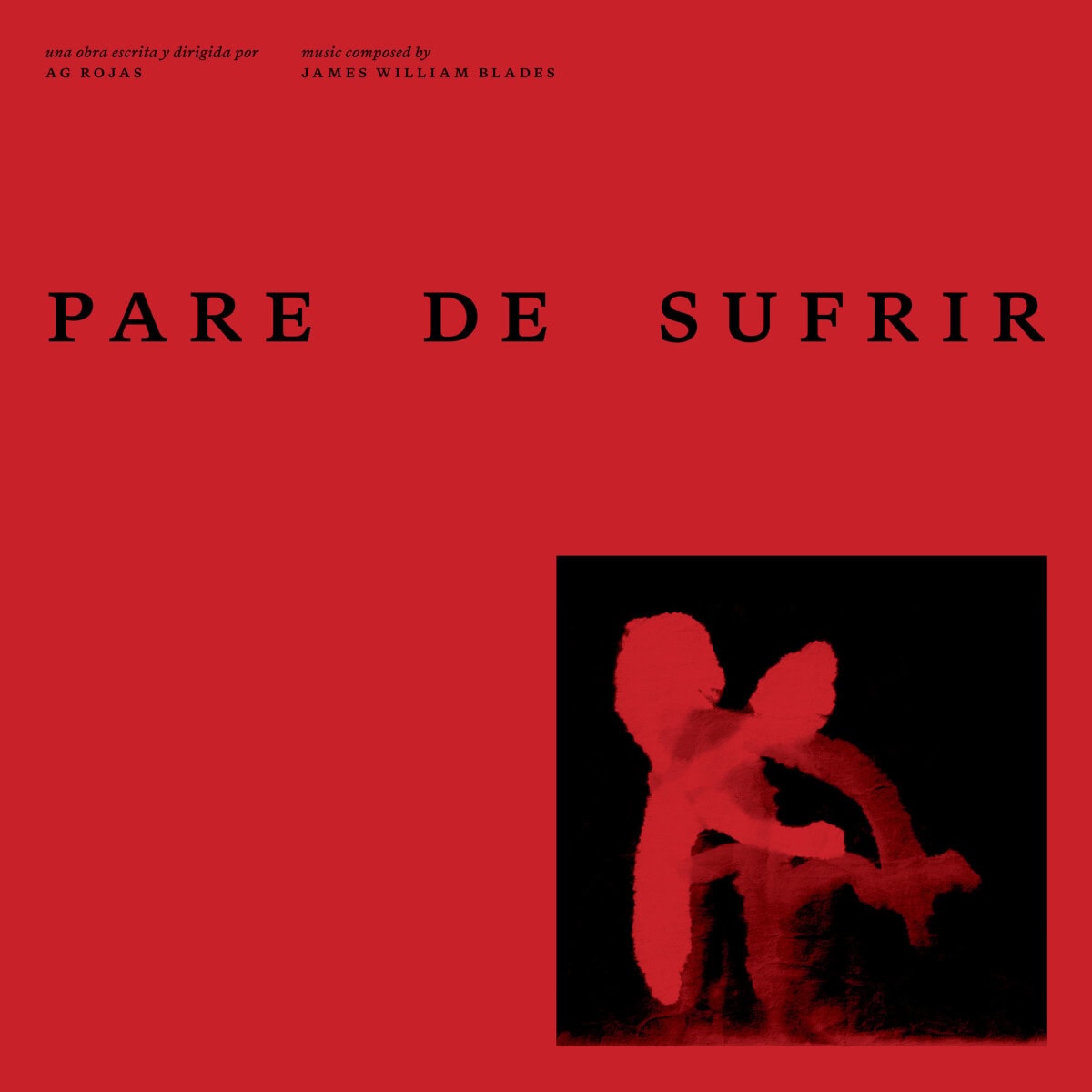

James William Blades Releases ‘Pare De Sufrir,’ The Score for A.G. Rojas’ Film

Album Artwork by Stephen Serrato

CREDITS

Recorded at: The Pool & Livingston Studios (London) TomTom Studios (Budapest)

Engineers: Billy Halliday, Marcus Locock (London) Tamas Kurina (Budapest)

Orchestrators: Oliver Mayo, Mitch Tanner

Studio Orchestra: TomTom Studios (Budapest)

Instrumental Soloists: Roman Lytwyniw (Violin Solo), Will Harvey (Violin 1), Calyssa Davidson (Violin 2), Yoanna Prodanova (Cello), Leo Melvin (Cello), George Cooke (Cello), Hat Wells (Clarinet)

Piano: James William Blades

Choir: Sigolo de Oro

Choir Master: Patrick Allies

Sound Design: Mike Regan

Pare De Sufrir is out now, buy/stream it here.

Today, artist, composer, and producer James William Blades’ score Pare De Sufrir is released via AD 93. Pare De Sufrir (translating to ‘End of Suffering’) is the official soundtrack to A.G Rojas’ film of the same title. Listen to & purchase Pare De Sufrir here and watch the film here.

Spanish-born, Southern California-raised filmmaker A.G Rojas is known for creating videos and working with the likes of Jamie xx, Gil Scott-Heron, Kamasi Washington, Spiritualized, and Mitski. Rojas’ sensitive eye and subjectivity has brought him from the world of music videos to creating his first independent film: a 48-minute featurette following three people as they navigate the liminal space between life and the afterlife in an attempt to heal themselves and each other. Rojas’ film is a fragile, wordless meditation on grief and how it can transform and baptize the body and spirit.

The almost silent film is a testament to Rojas’ trust in Blades’ composition to express the director’s voice and emotions. Rojas reached out to Blades after coming across his score for Keeping Time (dir. Darol Olu Kae). An intimate and unusual process unfolded. Rojas explained to Blades the personal narrative of the film, the two sharing unfurling conversations on the nature of loss and the human spirit. But Blades did not watch the film, and instead worked on instinct to build out a concept of how the score would unfold, shaping its operatic, textural, and granular tone.

Blades went on to record the score in full, with orchestra and choir, without going back to Rojas for feedback, aware that he was taking a complete risk. “It was definitely something I felt had a gravitational pull,” says Blades of the decision. The score’s pull is reflective of the process of grief itself, how its moods and memories oscillate up and down into the past and lost futures, Blades hitting all those spaces with diverse and stretching notes.

The piano holds the memories of Blades and Rojas’ grandmothers, who both had out-of-tune pianos sitting in an empty room. The Silogo-De-Oro choir sing throughout, reminiscent of the broken phonetics of grief, the build up and release of tension and the inability to articulate complete sound or words. The harmony stabilizes and then becomes distant, taking the griever away from the lushness of life and into the realms of loss, death, and dream-like realities, as mirrored in Rojas’ layered vignettes. As the score closes, the harmonies become richer and fuller, marking a return to life.

Understanding the power of sound to both respond to and drive narrative, Blades’ score weaves together field recordings, half-remembered conversations, choral movements, string arrangements, and electronic fragments into a nuanced and evocative whole.